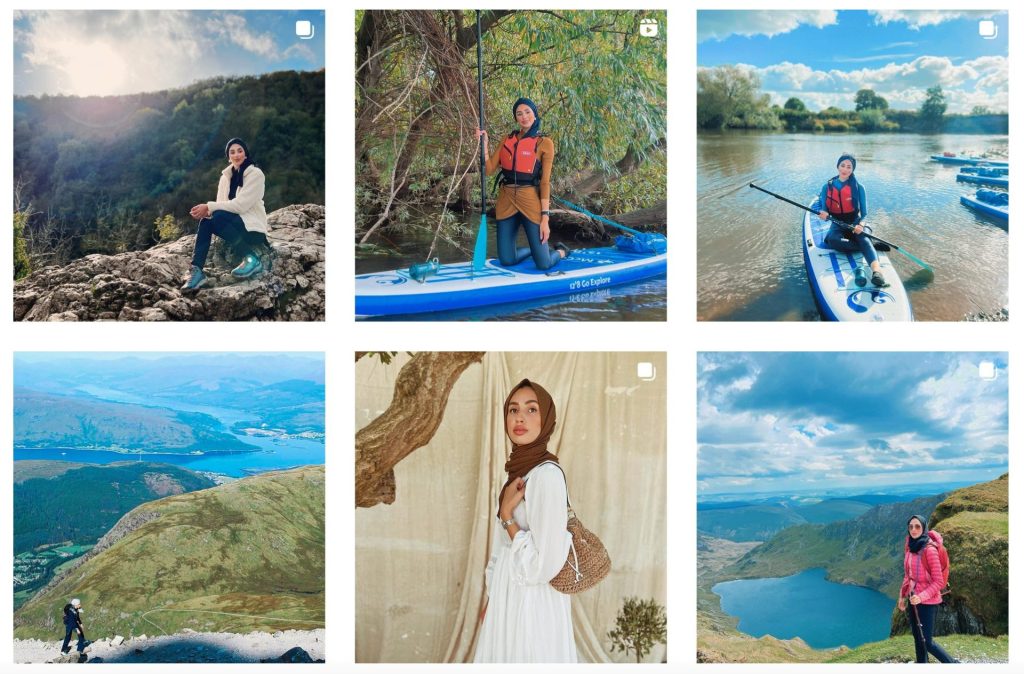

Muslim Hikers team leader, The North Face Ambassador, influencer and adventurer, Zahra Rose, shares her journey growing up in a lonely fisherman’s town and her lifelong curiosity for all things wild…

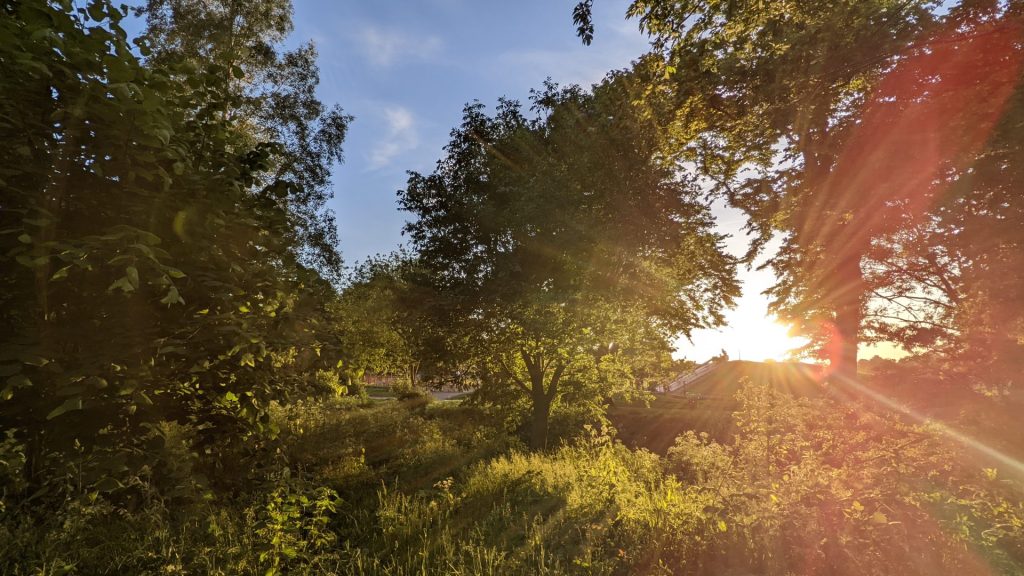

I sit here at twenty-nine years old, the winter sunset warming my face and the waves crashing against this pebbled beach I have grown to love so much. The wind occasionally carries the splashes in my direction; some make contact with my skin. I begin to reflect on how little I’ve touched these waters and yet how many souls make the treacherous journey across this very ocean every day for a better life.

Growing up in a seaside town has its perks: you’re surrounded by outstanding beauty, lots of greenery, cliffs, fresh sea salt air, seafood, and of course the crashing waves. The downside is that we aren’t English – there weren’t many of us around, we were a minority in a lonely little fisherman’s town.

Despite being born in England, this very town in fact, I was raised speaking my mother tongue, Arabic, at home. I didn’t speak English until I began pre-school, and so many of my learning experiences happened within the classroom. I recall much of my time, especially in summer, was spent in the school library with my plaid summer dress sweaty against my skin, the maroon leather chairs beneath me sticky from the humidity.

Missing out on the joys of ‘messy play’

I would hear screeches of joy seeping in through the windows from other children. While I learned vowels and how to construct sentences, they found worm holes and constructed dens. I recall the sadness I felt from missing out on the joys of experiencing ‘wilderness and nature’ classes and ‘messy play’ as I sat surrounded by the musky smell of neglected books.

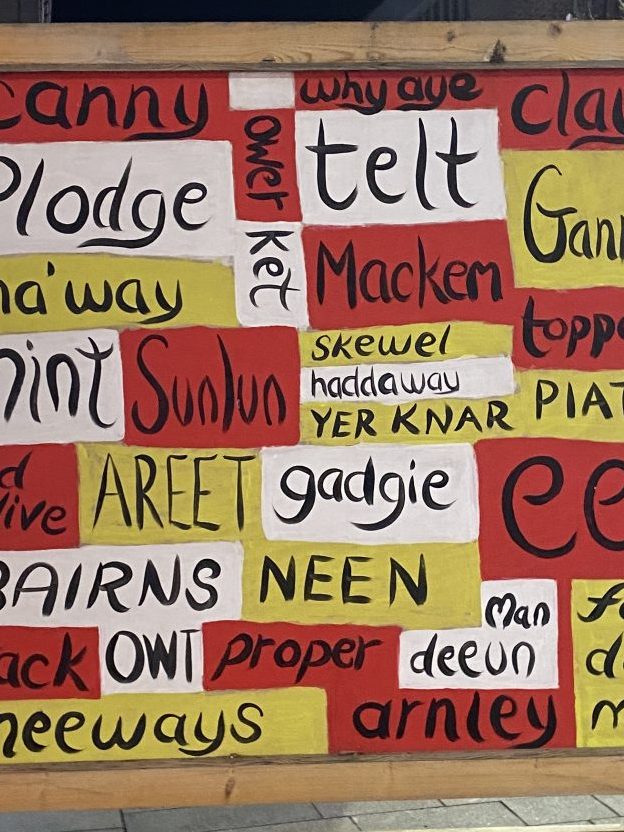

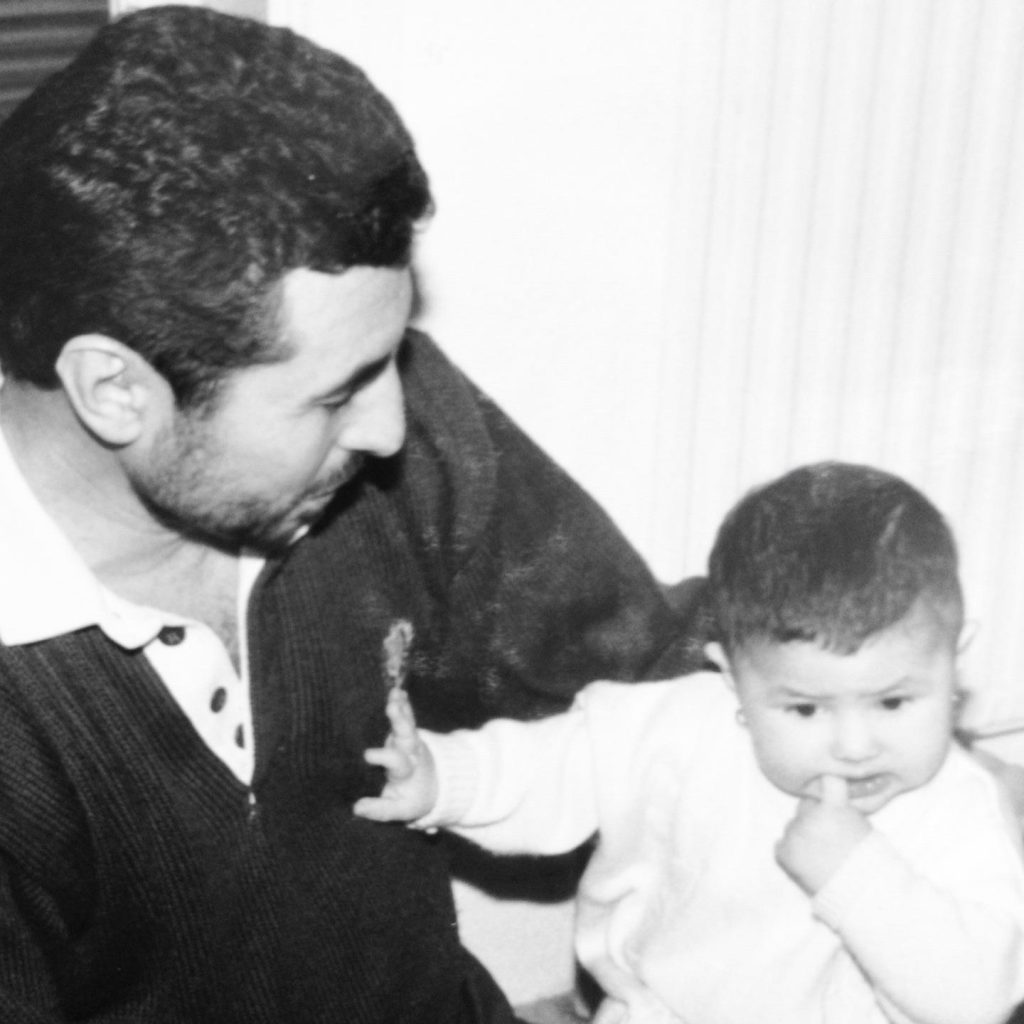

The boot room would be freshly matted with mud, and during lunchtimes I would overhear children speaking about ‘building hives’ and ‘catching tadpoles’ and ‘newts’ along with other words and phrases I wasn’t so familiar with. I would skip to my father at home-time, forcing my bookbag into his huge hands while I regurgitated everything I had overheard. “Baba what does this mean?” would be an everyday question. On the way home, while I climbed walls or raced my sisters, I would listen attentively as he would explain to me in Arabic. Occasionally he would pull out the Oxford dictionary in his office drawers when we got home, if there were words he too did not recognise.

I would run to him after supper to see his enlarged features behind the magnifying glass, sitting patiently waiting for me, so that together we could make sense of the world. I remember of all the words, the ones linked to nature were the ones that evoked the most curiosity in me: the words never stopped at their meanings. There was always more to learn, and these learnings would only strengthen my yearning to be in those outside classes instead of the library.

I would spend hours watching nature documentaries with my family after supper, the BBC’s Expedition Borneo being one I remember as such a pivotal point in my curiosity with hiking summits, rope work and adventure. I would often ask my parents about hiking, but it was unfamiliar and inaccessible territory to them. Walking for ‘fun’ or without purpose wasn’t really an ‘immigrant’ thing.

Walking for ‘fun’ or without purpose wasn’t really an ‘immigrant’ thing

It would be many years before I was able to experience nature outside of our large, long downhill sloping back garden, but with my family, it was always an adventure. The garden had concrete stairs trailing down the centre, with tall trees and plants hugging you either side, from the lavender and daffodils at your ankles and calves, all the way up to the four sky-high protected pine trees and a large oak tree which sat in the middle of the garden, dividing the upper half and the lower half. Although far from the Mediterranean, in summer it didn’t feel like it. My parents adorned the garden with fruitful tress, plums, cherries, vine leaves, fig, apples, pears… you name it, we had it.

Discovering nature in the garden

Summertime weekends, along with spring and autumn were spent out in the garden from morning until bed and bath time, even then we protested that the sun was still out! My sisters and I would find joy in pretending to present wildlife documentaries using the family camcorder, David Attenborough style of course. We would make ‘perfumes’ from my mother’s bay leaf tree and rose and jasmine bushes by crushing the petals using her beloved Greek pestle and mortar. We would secretly collect unripened fruits and veggies and create our own ‘dishes’ in a makeshift garden kitchen for the visiting animals. We would dig up bird and rodent skeletons using garden tools and paintbrushes like true excavation specialists. We’d catch frogs, toads and slow worms, and sometimes even make tiny ponds using plastic bags to line the basin and attract wildlife.

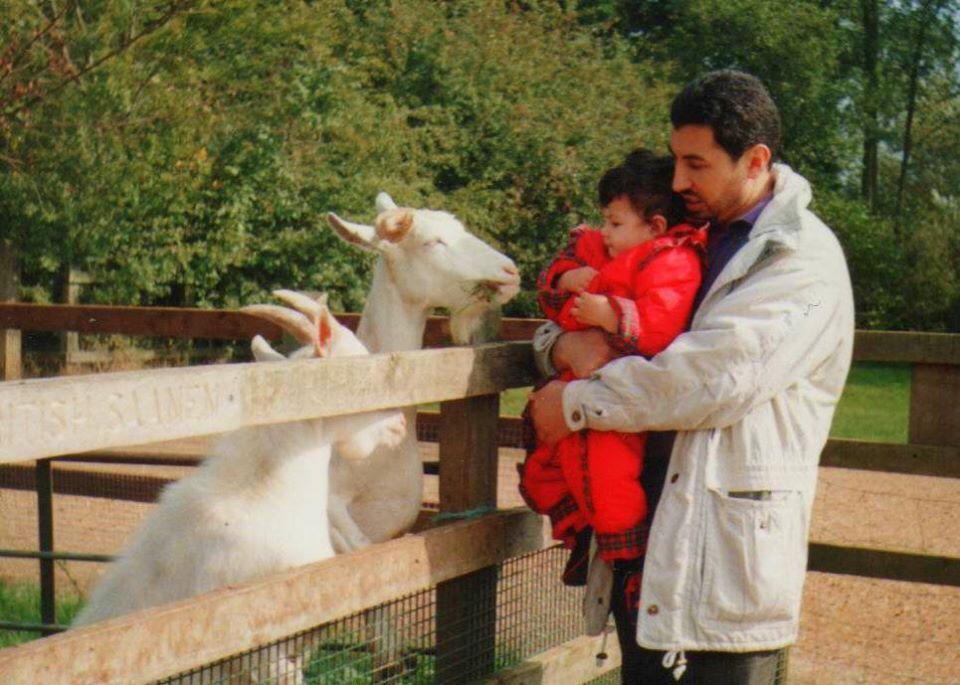

Once inside, we were in our element, part of the furniture, talking to the proud farmers about their stock, asking inquisitive questions, screaming at my parents to look at how ‘cute’ the tiny lambs and fluffy bunnies were

The garden backed onto a protected wildlife area; we would often pinch my father’s battered binoculars, which had worn the stain on the window ledge they perched on. We would crowd and snatch from each other to catch glimpses of goldhawks, owls and sometimes escapee tropical birds. Our combined love for bird watching led to us building a giant aviary one summer with my parents.

We would often end up at farm or bird shows at seven in the morning on a weekend. My sisters and I would be singing and dancing to Arabic music in the back of the grey Toyota Carrera as we pulled into these quiet village affairs, getting all those curious looks that we had grown accustomed to. Once inside, we were in our element, part of the furniture, talking to the proud farmers about their stock, asking inquisitive questions, screaming at my parents to look at how ‘cute’ the tiny lambs and fluffy bunnies were. Eventually one weekend we ended up leaving the village hall with a faded vintage yolk-yellow incubator, with capacity for forty eggs.

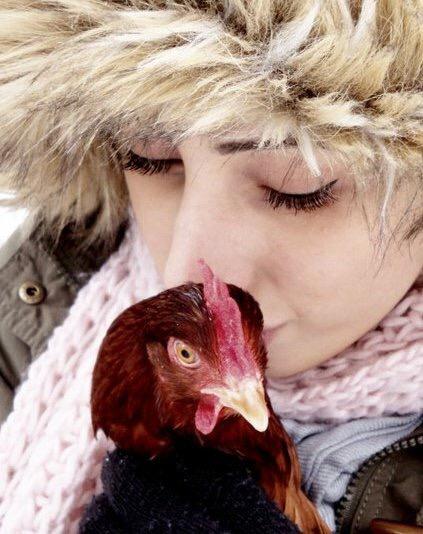

Chickens in socks

We spent the journey home prodding my parents about how baby birds were made. After much hesitation we settled for “you buy an egg, put it in an incubator and after twenty-one days a featherless chick breaks through the shell.” We could barely contain our excitement at this point; despite our age we were very knowledgeable on the varieties of chicken breeds and could not wait to fill it. I spent my pocket money on the most adorable looking chickens: the ones ‘with socks’, Brahmas and Silkie Bantams. My sisters and father added Sussex lite, speckled Sussex, redcaps and many more.

My parents encouraged us to add some supermarket eggs into the mix as an experiment. Sure enough, after twenty-one days, on my sister’s birthday, we ended up with eighteen little varied fluffy yellow chicks. Some needed a hand breaking out of their shells, while others bulldozed through; all the while we sat around consuming our daily meals while peering through the little window at the top in awe, admiring God’s creation.

From the mountains to the seaside

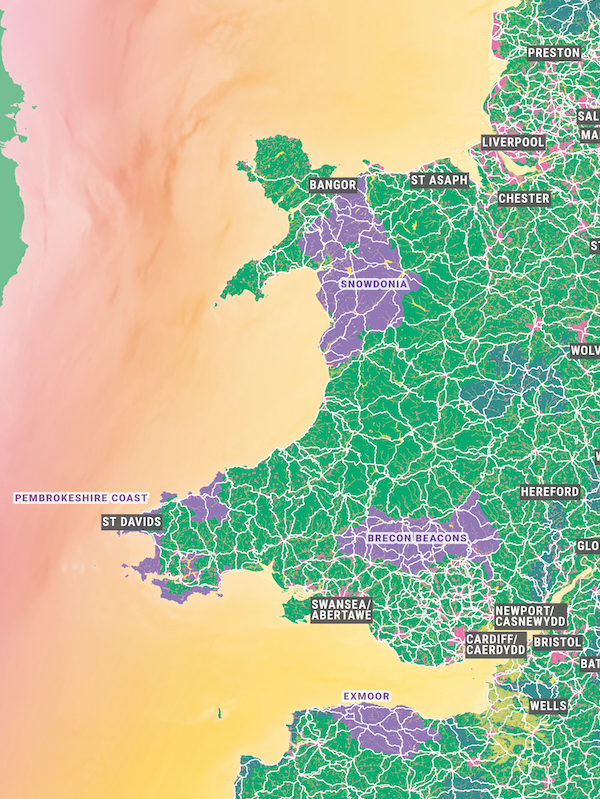

That was the moment I truly fell in love with nature, despite not yet seeing or experiencing very much of it outside of our garden and TV. Something about seeing the start of life happen in front of me forged a connection and desire for more of it. A lot more. My adventures took me to Mount Everest, K2, Kilimanjaro, Ben Nevis, the Peaks and Wales. This was before I explored the precious seaside town I was born and raised in.

Like most full-circle moments, during lockdown I ended up walking a lot more. I found myself retracing my childhood at local parks, the marina, our garden and beach, often slowly discovering places I had never been despite calling this place ‘home’ for almost thirty years. One afternoon, I ventured beyond the usual routes and found myself perched on a coastal cliff, watching the waves calmly bouncing against the yellow rock beneath me. I looked at the path behind me and realised that walking is perhaps life’s greatest adventure. What’s more, I found people like me out here too.

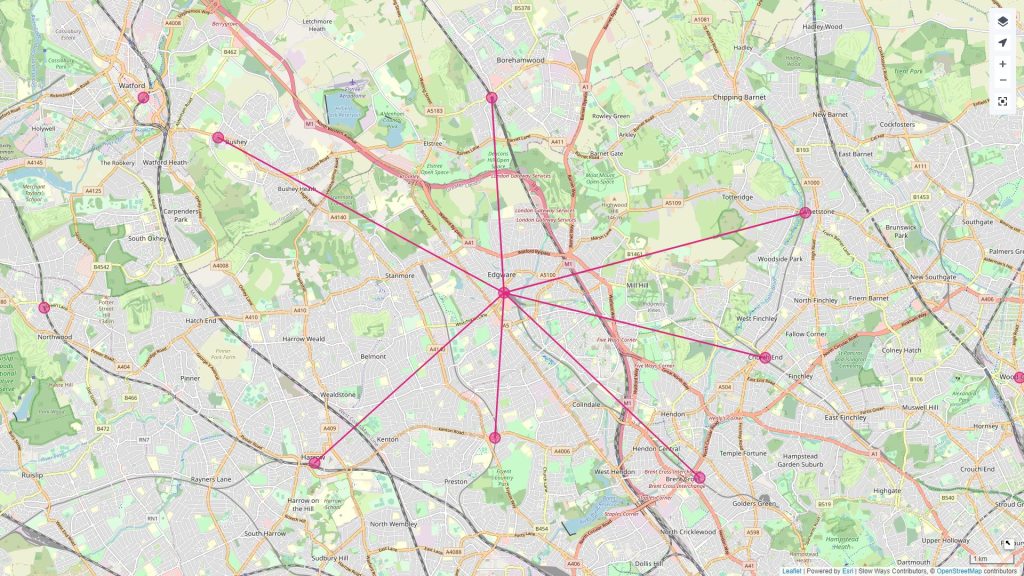

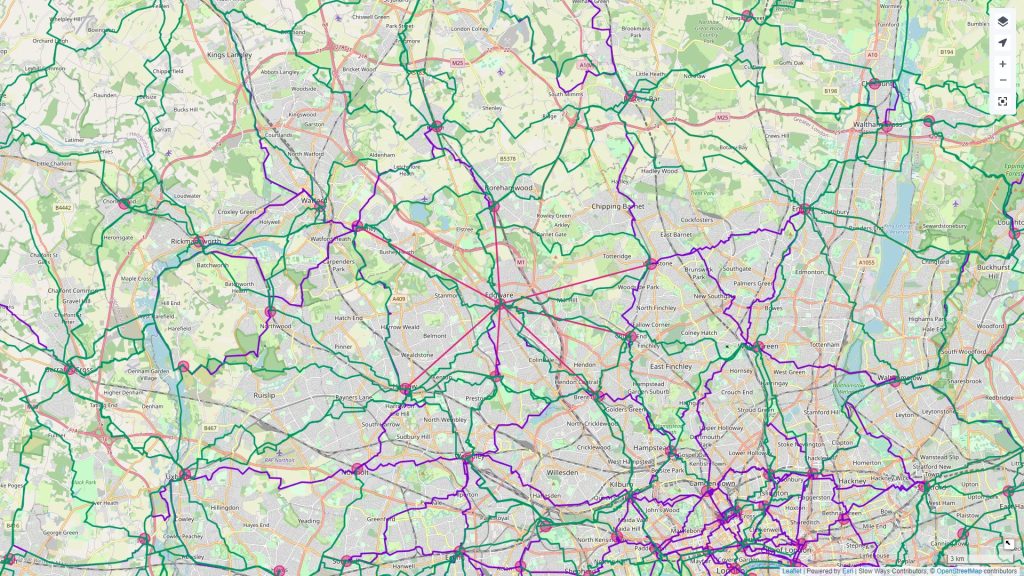

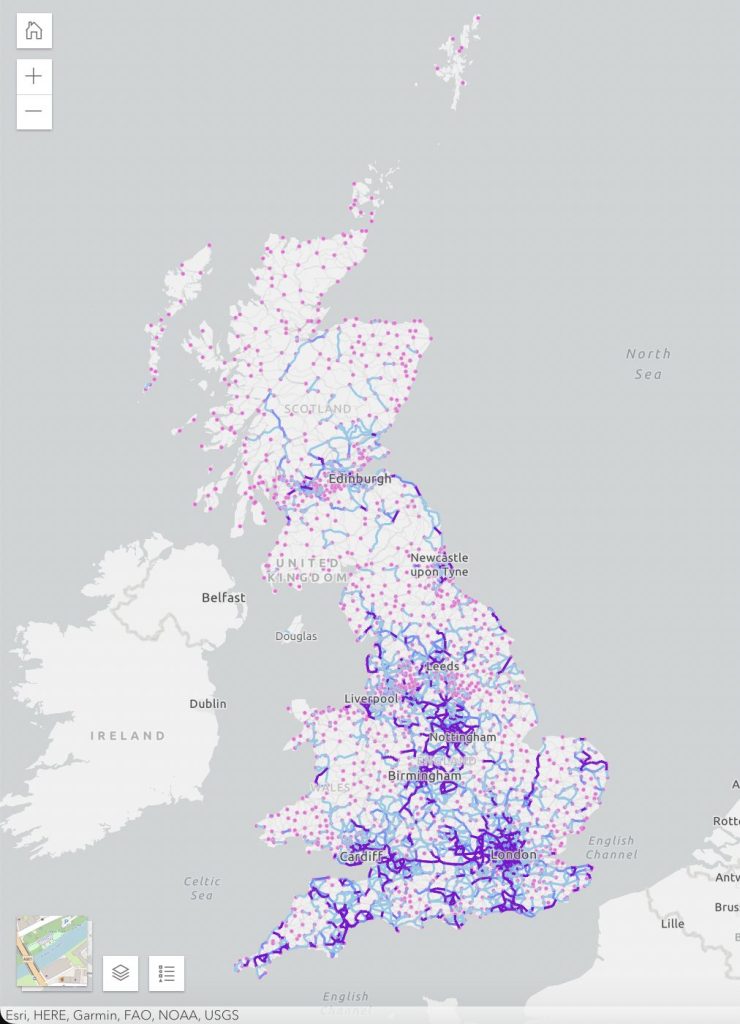

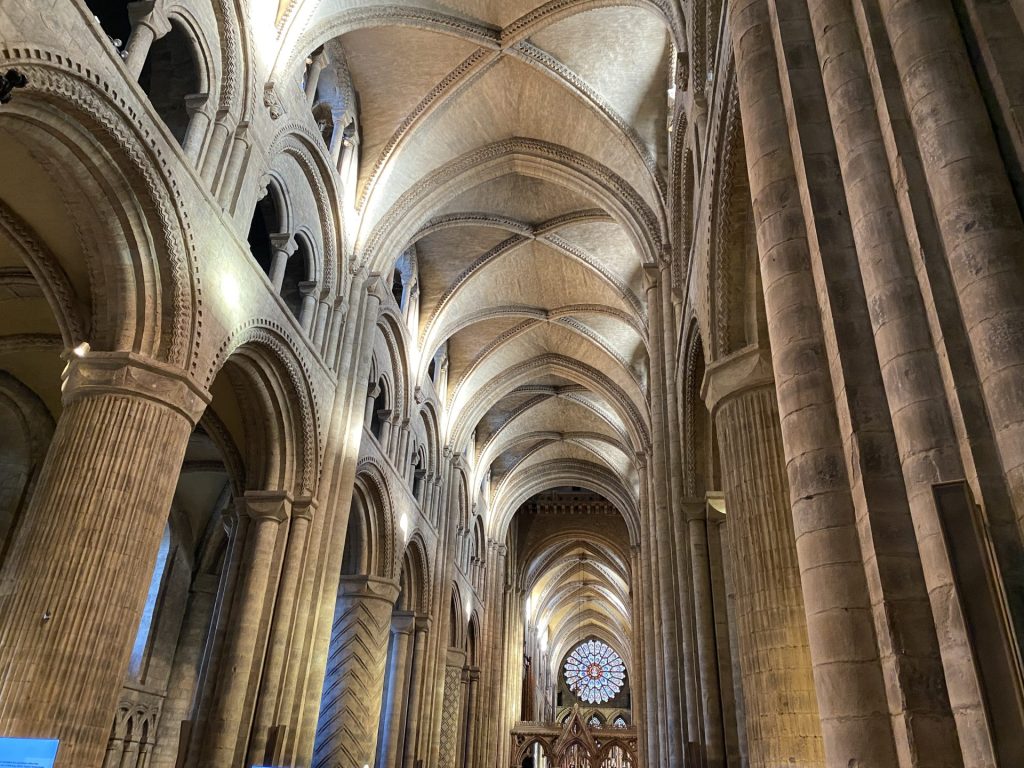

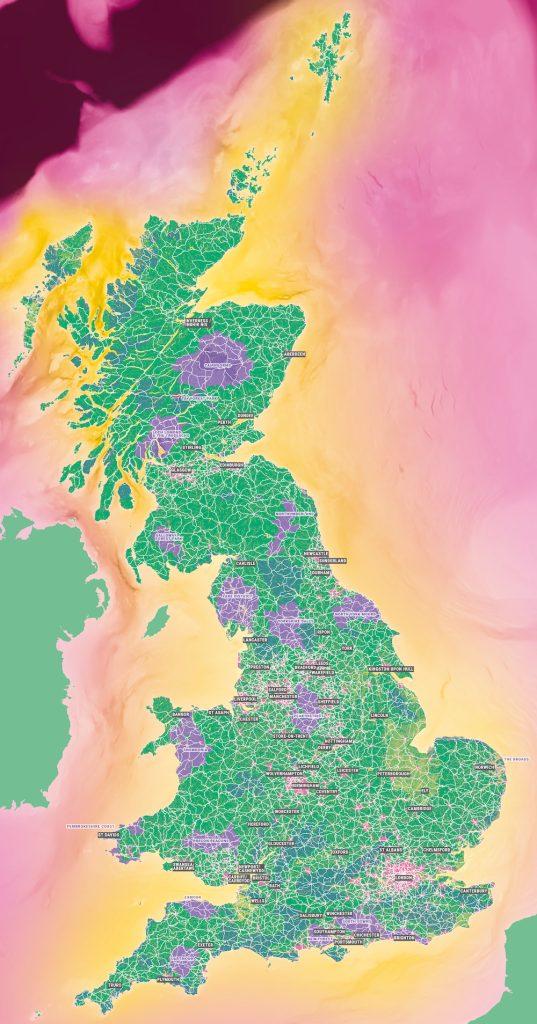

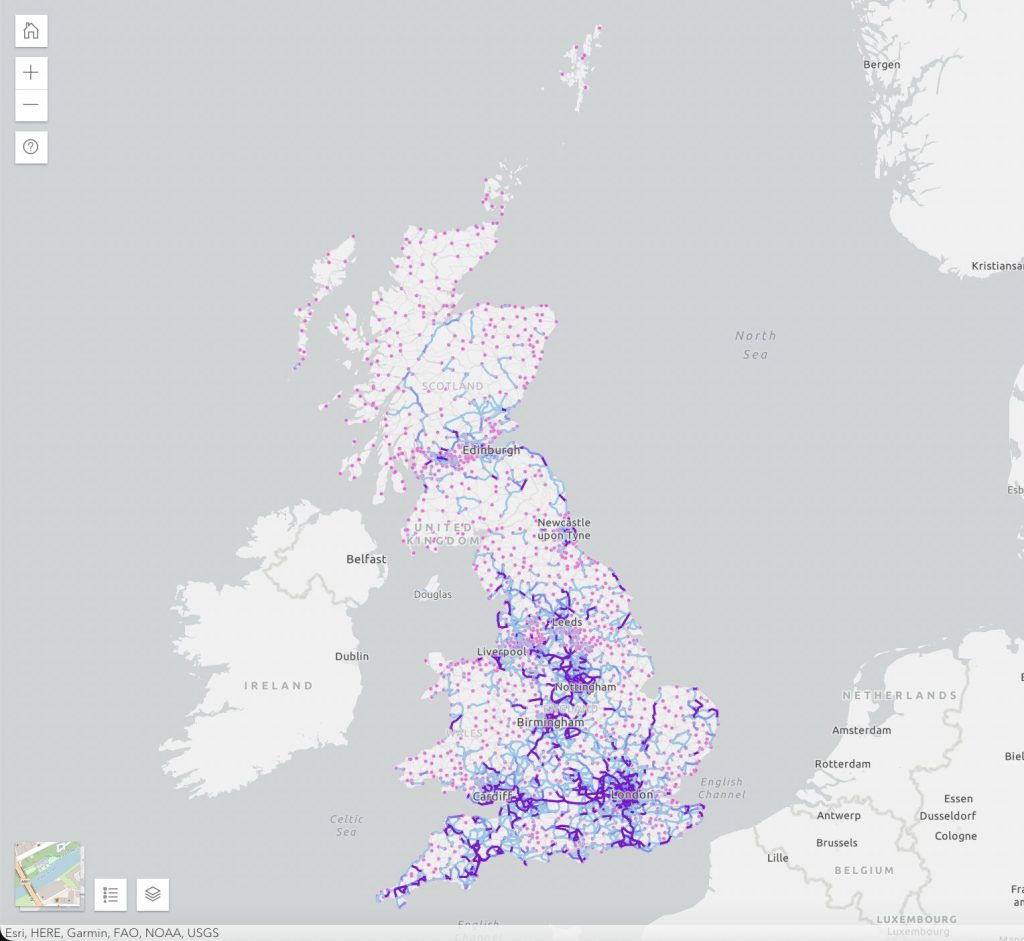

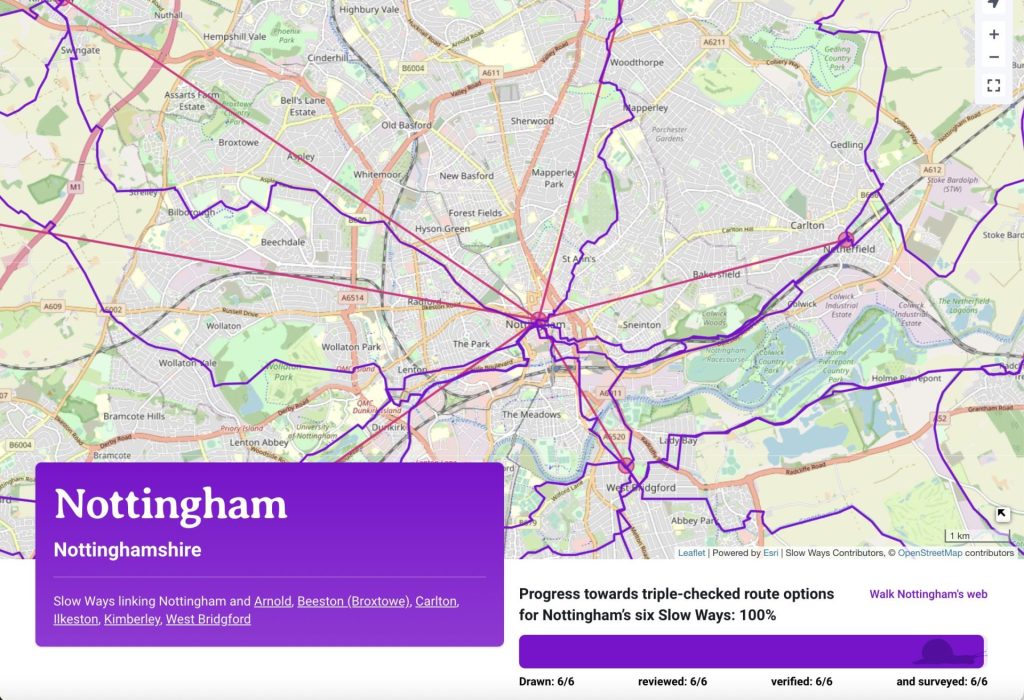

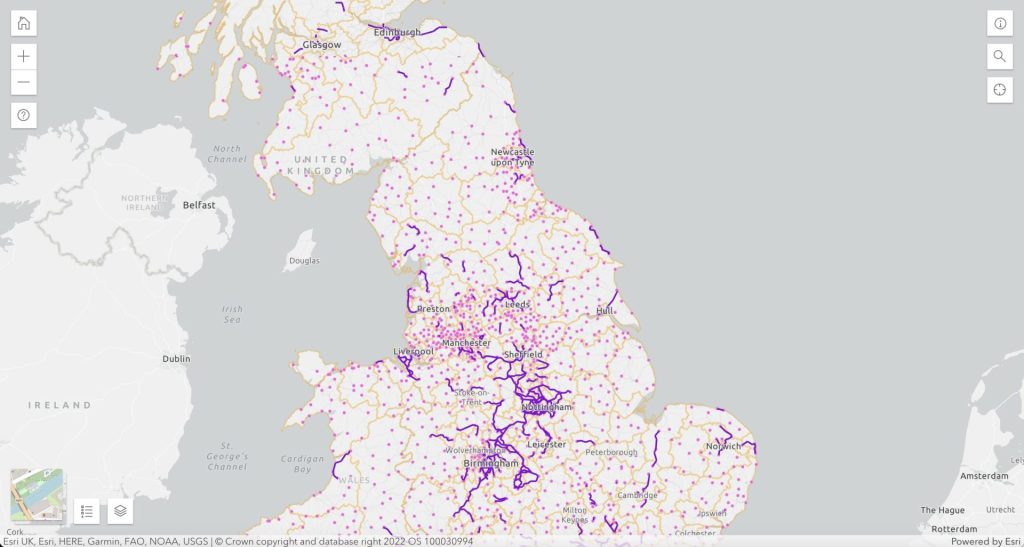

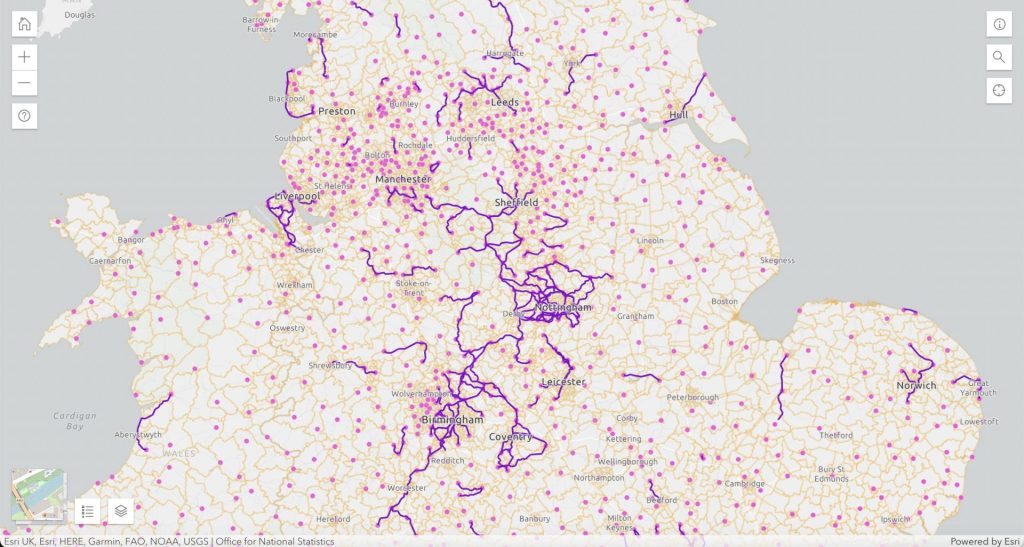

Slow Ways were really pleased that Zahra led a walk for us during the Leicester swarm in autumn 2022. We’ve got more led walks coming up during our Summer Waycheck in June this year – see here for more and to sign up.

Zahra Rose

I’m an avid hiker and lover of the outdoors, sometimes an adrenaline junkie. I’m a member of the @Muslim.Hikers team. I have trekked Everest, K2 and Broad Peak base camps and summited Kilimanjaro. I have just signed up to my first half and full marathons this year with many more adventures to come.