On solitude, slow ways and choosing the path less travelled

I’m not sure why I chose Great Yarmouth as a hub from which to walk Slow Ways. It was a random and spontaneous choice, as are most of my location choices for story expeditions. A few days before I set off, I had been looking over the National Parks trail that snakes its way across Great Britain and my eyes settled on the Norfolk Broads. I pictured big skies, rugged wetlands, and wildlife. I pictured flat ground, and ease.

There is a certain amount of hope and faith that comes with walking Slow Ways – a hope that you will reach the destinations you set out to reach, and faith that the journey will reveal itself to you, perhaps in stages, or perhaps in a single moment. For me, there is the added hope that stories will surface along the way and that my findings will bring about a sense of renewal, inspiration, wisdom and connection. So far this has been the case with all my Slow Ways journeys – each one has been made up of a mosaic of pathways, places and people that have rendered a geographical area so unique. I wondered on the train ride up what this journey would be like.

It was only when I arrived that I saw the sad irony of choosing Great Yarmouth as a destination. There I was alone in a Great British seaside town crowded with large families on their summer holidays. Grandparents, aunts, uncles, mums and dads and children… so many children. It felt like an unnatural place to be by myself, more so since I’d just split up from my partner. We wanted different things. He wanted a family, and I didn’t, so after a time we parted ways.

Arriving at Great Yarmouth

As I arrived at the train station, I tried to quickly familiarise myself with my surroundings. I brought up a map on my phone and started to walk towards the north end of town, where the family-owned bed and breakfast I would be staying at was located. The centre of town was noisy, colourful, brash, on the fringes of a watery, remote, and wild expanse. I walked down a very long road. I passed by a cemetery and convenience store until I arrived outside the iron gates of the BnB; on them the names of the owners were carved in iron. Jeff and Helen.

I met them both, they were lovely. They told me that an elderly ironsmith from Sheffield who had stayed at their BnB had gifted them the gate. He even came down to install it. We talked for a bit; they told me that they moved to Great Yarmouth 17 years ago and I told them it was my first visit. At the end of the conversation they asked me to let them know what I’d like for breakfast the next day and pointed at my table, a small table for one in the corner. They also gave me a list of rules.

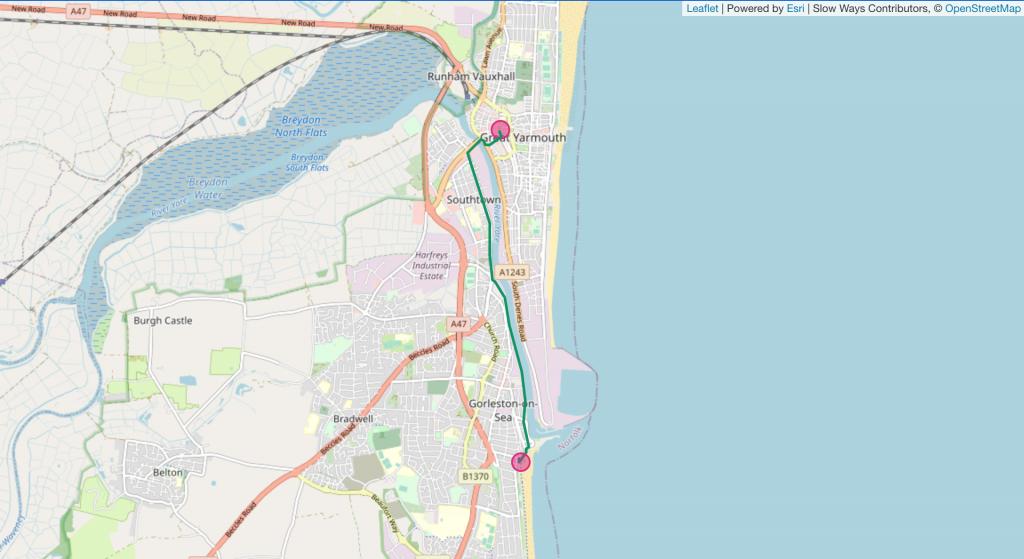

I went up to my room and scanned the list: phones and electronic devices are not allowed in the dining room, night-clothing must not be worn in communal areas, strictly no smoking. I put the list away. I decided I liked Helen and Jeff. They were warm, but straightforward. Over the next few days I found this to be the case with other people I met in Norfolk. I unpacked a few things, downloaded my first route and opened it up on my OS map app – it was an easy one from Great Yarmouth to Gorleston-on-Sea.

Great Yarmouth to Gorleston

It was an overcast afternoon, and I walked to the starting point of the route along the sandy beach before heading inland and crossing a bridge over the river Yare. The route was straightforward. I passed several giant grey and brown industrial estates. I passed a petrol station, some warehouses, cottages, parrotdise, and a lighthouse before arriving at the finishing point, the next beach south.

I enjoyed a pack of Scampi Fries and a bottle of Lilt and took in the views before heading to the High Street. Traversing different geographical areas often felt like entering new worlds. It started to rain. I walked pass a house with a UKIP sign on it. I walked pass the Conservative Club, Palace Cinema, a faded Blockbusters façade, a butchers’, barbers’ and tailors’, before arriving at a bus stop.

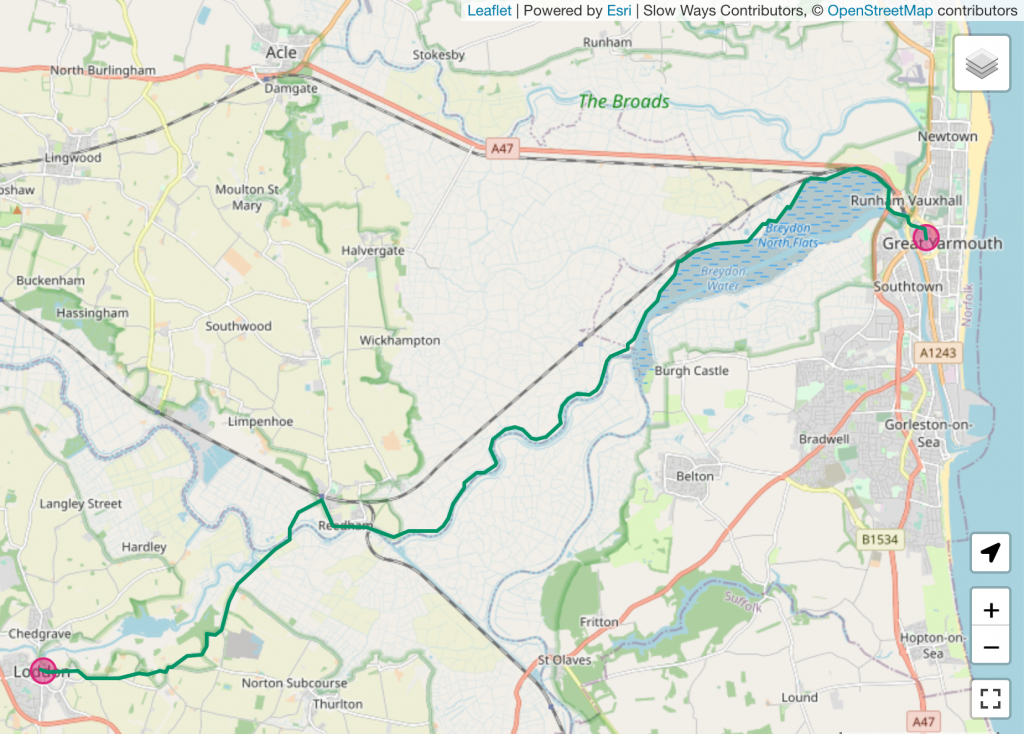

Great Yarmouth to Loddon

The next morning I went down to the dining room for breakfast. I was planning on walking to Loddon. “I googled it, 17 miles!” Helen exclaimed, slapping me on the shoulder animatedly as I went to take my seat. I’d told her of my plans the previous day. “You could just walk to Berney Arms”, Jeff suggested. “It’s lovely there!” I told them I had to walk the whole route for work. They didn’t really understand. “Well, you’ve got my number,” Helen said before going into the kitchen to make me breakfast.

The middle-aged couple sat on the table beside me struck up a conversation. The lady told me her stepfather had recently died, but her mum told her not to cancel their trip. They used to come up to Great Yarmouth every year for nine years, until covid that is. This was their first time up in three years. She told me they liked the beach; they’d play crazy golf and go to the dog races. They lived in Colchester in Essex. I find it fascinating, the way in which people will reveal things about themselves, sometimes slowly and other times in one go. We skim over lives through fragmented chats over breakfast. I’ve always felt like a stranger in the lives of those around me, someone to whom others could easily share things about themselves. I’ve always felt like a ghost in my own.

After I finished eating, I excused myself and got ready to go on my walk. The route began by the river Yare where it led me into the wild and beautiful broads. I’ve always loved wetlands. I worked at the London Wetland Centre for years and, after that, did a stint at East Reservoir, now Woodberry Wetlands. There’s something so magical about them – the way the reeds fall and the water kisses the earth. I loved the solitude and the space – for the first five miles I didn’t come across another person. I passed cows and ghost windmills, starlings flew overhead, and egrets dawdled in the water. I felt free, and feral and surrounded. There were so many flying insects, butterflies, and damselflies.

I love being alone in the wild and I love being alone in the city, but in the city the aloneness sometimes feels jarring, pronounced – noticeable. The path was overgrown in parts, there were holes in the uneven ground. I paid attention to it. I walked through the marshes of Berney Arms, and onward to Reedham. I came by a family, sitting at the water’s edge. We exchanged hellos. “Bet we’re the only people you’ve seen!” the man exclaimed; I nodded.

Nine miles later I finally arrived in Reedham. I found a tea shop by the river where I charged my phone and enjoyed an ice-cream and panini before continuing. The station was closeby – I could call it a day and do the rest tomorrow. After a hesitant mile, I decided I would commit to the entire route. I would go the distance.

I walked towards the ferry. It cost me 50p to cross the river. The ferry operator, a young man named Luke, asked me if someone was picking me up from the other side. I told him I was walking to Loddon: “You be careful,” he said ominously, and repeated it when I got off the other side. I nodded and smiled politely. Grey clouds covered the sky, and I began walking up the road towards Loddon, passing by roadkill; a dead pheasant, a dead gull, a dead hare. Whenever I heard the rumble of a car I walked close to the edge of the road and paused to let it pass.

There were no other pedestrians, and I began to understand why the ferry operator told me to be careful. I crossed a wheat field, a bridge over a stream with missing planks of wood. Eventually, I arrived at a cemetery on the edge of town. I walked to the bus stop in Loddon and waited for the bus to Norwich to arrive.

It was strange arriving into Norwich. The man I have been seeing is a barber; he had lived in Norwich for nine years before moving to Brighton. He said it was a fateful decision, he would either open a new Turkish (actually Kurdish) barbers in Cornwall or in Brighton. On a whim he decided on Brighton. It seemed like a cool place, he said. I liked his haphazard and random decision making – it resonated with me. It’s strange how places shape you. His interest in tattoo artistry (every second person in Great Yarmouth had a tattoo), his manner of interaction, his way of seeing the world – it all made more sense in the context of this place he called home for just under a decade, Norwich.

On the bus from Norwich to Great Yarmouth, thoroughly exhausted, wistful but enlivened, I felt gratitude for all the places that had shaped me, and the paths I’d taken (and not taken). There are so many paths, leading to so many different destinations – and on the way you come by terrors (wild things jumping out of bushes, dead creatures, a car approaching on a road with no verge) and delights (a hare jumping along a flower shrouded path, deer, a panini, a lighthouse, and golden beaches). I wondered where my next journey would lead me.

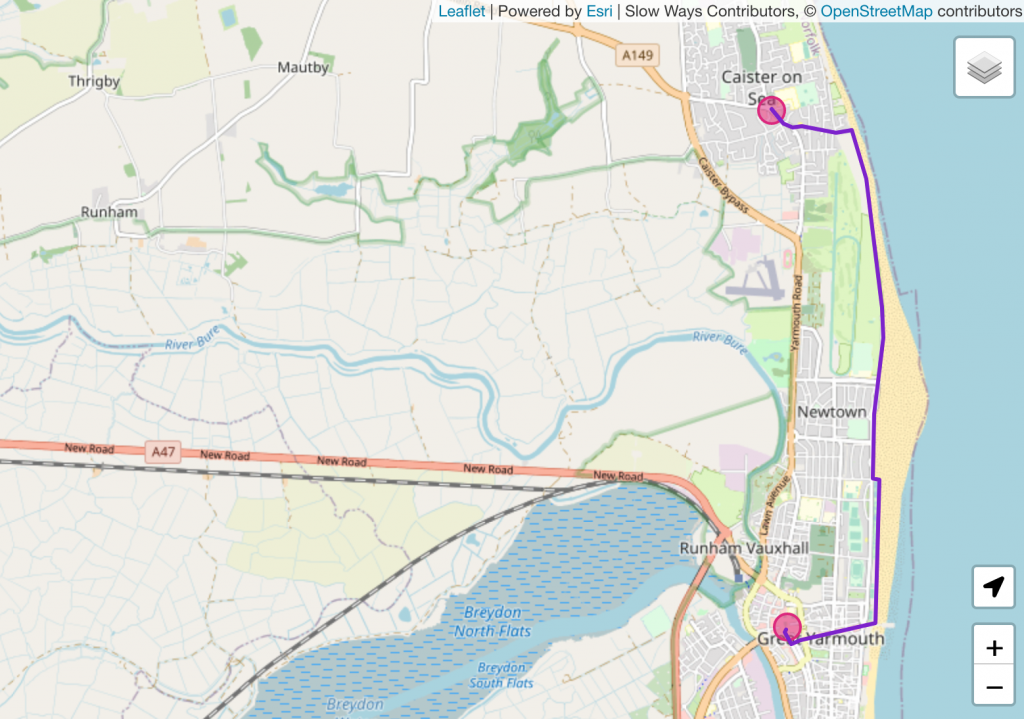

Great Yarmouth to Caister

The next day, my legs hurt. Helen was happy that I’d made it, and so was Jeff. There were a few new people in the small dining room, others had left. I spoke to the couple I had spoken to the day before. They told me they enjoyed the day mooching about. I liked that. I wanted to do that. Mooch about. I missed mooching. I decided I would walk one more Slow Way and then spend some time in town among the crowds that I had so carefully avoided.

That morning I received a message on Instagram, where I was posting about my walks, from a local Slow Wayer Genevieve, asking if I wanted to meet up. Unfortunately, we couldn’t find a time that would work for both of us. I asked if I could get in touch when I got back to Brighton as I’d love to learn more about life in Great Yarmouth and she agreed.

I walked to Caister. The route had already been verified but I was curious to visit another nearby town. I decided to take a detour and walk along the beach. The sun was shining, and it was mostly empty. I took off my shoes and socks and walked along the shore, enjoying the feel of the cold water against my tired feet. After a bit I re-joined the path and walked into town. I passed a holiday park busy with families, I passed by the open library. It was closed to non-members. I passed Caister Social Club. Caister men never turn back, a plaque on a wall painting read.

I got the bus into town and walked towards the beach, past the fish and chip and sweet shops. It was bustling. At the beach, children went on donkey rides and families were having picnics. I walked along the promenade, pass the Empire and Joyland, and the horse-drawn carriages.

I went into a café to try to work. A young Greek man sitting beside me asked me what I was working on. I told him I was writing a walking story. His name was Andres. He said he had lived in Great Yarmouth for a number of years. He said it had improved a lot, the infrastructure. He asked if I’d seen the murals around town and I told him I hadn’t. He told me he helped create them and that he was an aspiring artist. Normally I would have asked a dozen questions, but my mind was wandering, and I felt tired in every sense, reserved and inside myself. I left; I felt listless and decided to walk to the bus station. I got on a bus to Lowestoft.

Lowestoft

I’d never made it up as far as Lowestoft, the most easterly town in the UK. I spent a lot of time in my early twenties exploring Suffolk. Often based in Ipswich, I’d wander around Snape Maltings, Aldeburgh, Woodbridge, Felixstowe, Dunwich Heath, Southwold. Suffolk felt familiar.

I’d only been to Norfolk once before, years ago. I travelled in late September and volunteered at a youth hostel in a former monastery. I spent my mornings serving up breakfast and making beds, and the rest of the days reading books on solitude and wildlife in a local library and walking along the Norfolk coast. I’d visit beautiful quiet places like Holkham, Salthouse and Weyborne. Great Yarmouth was very different to those sleepy seaside villages, home to older communities. It was different, not in a good or bad way, just different.

When I arrived in Lowestoft, I wondered down the high street, by the marina and towards the beach. It was a lot quieter than Great Yarmouth. I wandered by South Pier and Claremont Pier. I watched the seagulls and ate an ice-cream. I people-watched and thought about all the work I still had to do, all the emails that I hadn’t responded to, stories I hadn’t edited and social posts I hadn’t scheduled. But looking out at the sea, watching children build sandcastles and adults nap on the deck chairs – none of it seemed to matter. I was on my own strange summer holiday, work could wait.

Going home

The next day I had breakfast, said goodbye to everyone and checked out. I walked to a Premier Inn on the other side of town beside the river Bure and asked if I could leave my bags in storage. The man at the desk kindly said I could. On the way back into town I spotted a sleeping stray cat and lingered for a few moments to watch him. I wandered aimlessly the way I would do in my pre-Slow Ways days; I wandered by the markets, the gardens, the parks. I lay down on the sand at the beach and looked up at the sun and let time slip away. Eventually I settled in a café in the shopping centre and began to catch up on work. My train wasn’t till the evening. When I finally went back to pick up my bags, the cat was still there. He followed me for a few metres before parting ways.

I got on my train. I’d completed another Slow Ways journey. I thought on the lessons I’d learnt. I’d learnt how to tread uneven ground; cracked earth and sinking sand – stumbling onwards. I learnt to trust the journey. I learnt (and I come back to this learning time and time again) that it’s okay to go it alone, and to choose the path less travelled. In doing so you make it easier for others to do the same.

I was reminded to lean in to where I am, and perhaps most importantly, to be as present and intentional in my life as I am on my Slow Ways journeys.